To attempt creating, let alone staging, an opera about a 14-year-old Black boy’s execution requires near superhuman artistic power—along with heaping doses of audacity or guts. More likely, Frances Pollack, the young composer of “Stinney: An American Execution,” simply felt driven to dramatize the heinous event in 1944.

To attempt creating, let alone staging, an opera about a 14-year-old Black boy’s execution requires near superhuman artistic power—along with heaping doses of audacity or guts. More likely, Frances Pollack, the young composer of “Stinney: An American Execution,” simply felt driven to dramatize the heinous event in 1944.

Whatever “it” was that led her to revisit George Junius Stinney Jr.’s murder-by-electric-chair, Pollock executes—word choice intended—precisely what she set out to do: deliver an emotional sledgehammer.

Part opera, part musical, part straight-ahead (and violent) dialogue, Pollack’s work takes plenty of risks—at least as daunting as her decision to create the piece, which Greenville, South Carolina’s Glow Lyric Theatre mounted after the February world premiere.

The story, set in a South Carolina hamlet, begins with Betty June Binnicker, 11, and Mary Emma Thames, 7, wandering off to, of course, “the other side of the tracks.” They’re there to maypop flowers, the delicate, pinkish-lavender blossoms also called the passion flower.

Soon, an intensely creepy ensemble, all dressed in black, hooded rain garb gather round Betty June (Miranda Lee, whose emotive performance never wavers). The ghastly group, haunting and daunting through a lot of reverb, signifies, of course, The Grim Reaper. Meanwhile, offstage, Mary Emma (Kaylyn Shelton, equally stellar) is also raped and bludgeoned, we learn later, near the tracks.

The ghouls gambit feels off-putting and drags a bit, but the device does manage to convey the notion that, dear god, the girls’ suffering dragged on, too—needless to say, considerably worse.

Another example of a risk that sort-of works: after their mutilation, the girls return as angels. Now, they’re regular presences who, (super)naturally, can’t tell authorities that young Stinney didn’t kill them. And later, they comfort the doomed boy in his jail cell.

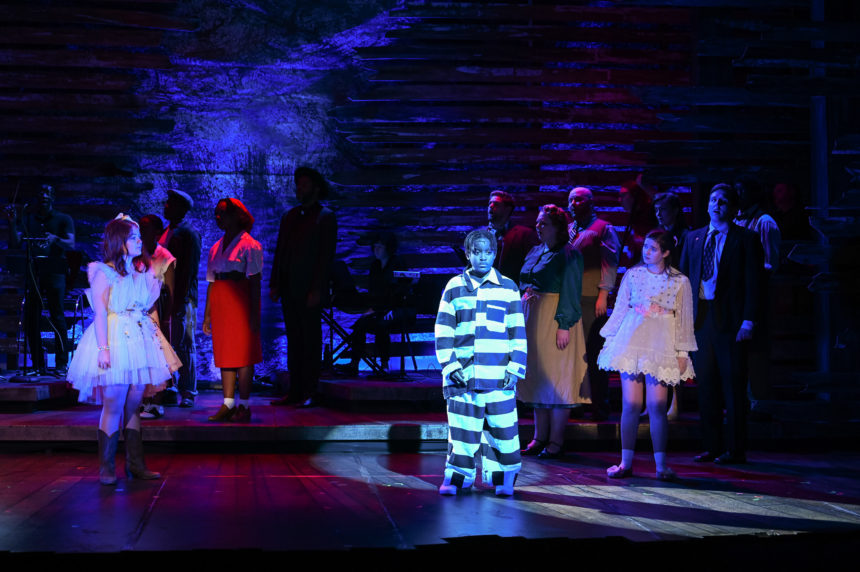

In those scenes, the risk works. That could be because the girls are roughly the same age as the titular character. whose Gavin Rector, in his Glow debut, rips you apart.

Radiating innocence and beauty (he’s a model, too), Rector handles with remarkable poise and depth the excruciating role of the youngest person ever executed. He offers up fear, anger and grace with admirable restraint. More notably, as thousands of volts fry him, he smiles, even laughs, in a brilliant display of joyful release.

It feels as if Rector’s turn added that much more inspiration to the entire company.

The boy’s parents—tenor Khary Wilson as George Stinney Sr. and Shanelle Woods, mezzo, Alma Stinney—provide near Biblical performances, vocally and physically. Another cast standout (among others), Dean Clarkson lends his tenor and intimidating height and presence to a policeman whose corruption is palpable and horrifying.

Such star turns certainly make life easier for co-directors Jenise Cook & Jenna Tamisiea Elser, while the music director, Byron K. Black, leads an orchestra that allows the actors to do their work.

With ear-wormy songs enveloping brutal-to-hear dialogue, the show is as tough to watch as it is of paramount importance to see it. Just heed George’s final words, an appeal Rector offers quietly and plaintively to his executioners: “I hope people stop being scared when I’m gone. Yes, sir, I’m ready.”

-John Jeter